This article is from the Applied Science Student Project Spotlights.

Ansel Hait, John Matheson, Ansen Ramsawmy and Kim Ristimaki

- Community Partner: Gitksan Watershed Authority

- Degree: Bachelor of Applied Science

- Program: Mechanical Engineering

- Campus: Vancouver

Our design process and challenges

We enjoyed taking something from an idea to reality and operating the lathe and milling machines to build our product.

At the start of the project, we met with stakeholders that included some of the operators of the fish wheel, members of the Gitksan Watershed Authority and representatives from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. One of the main criteria that emerged from this discussion was the need to create a solution that could be assembled using conventional hand tools and installed directly on the existing fish wheel.

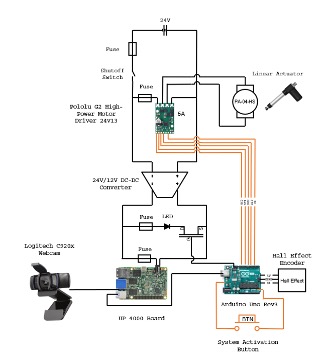

One of our first design decisions was determining how we were going to sort the chinook salmon – which are larger fish – from the sockeye salmon. We debated using a weight-based solution, but in the end decided that a machine learning system would be more reliable. The computer vision algorithm we developed detects the length of the fish and based on that makes a prediction of whether it is salmon or chinook.

Our final product consists of three main assemblies. It includes an inlet chute that is mounted to the arm that holds the fish wheel and is made of sheet metal to direct fish to the fish sorter. The fish sorter contains a tray mounted on a shift with the linear actuator and a lid with a mounting position for the camera. The final assembly, the electronics enclosure, incorporates the electronics components and is mounted on the side of the live tank.

It was challenging to do the machining work and build the physical structure. But it was really fun too. The machinists at UBC were great and taught us so much: they have a ton of experience and gave us just the right amount of guidance while letting us figure things out for ourselves.

Our project’s future

If the live testing goes well, we hope that the structure will be installed at the fish wheel near Big Bar. It can then start sorting out the sockeye salmon so they can be transported upstream and have a better chance of spawning.