UBC concussion study could pave the way for safer hockey

A high-tech mouthguard worn by UBC Thunderbird hockey players will record every big hit of the upcoming playoffs to capture data for UBC researchers who study concussions.

The study is led by Dr. Lyndia Wu, an expert in brain injury biomechanics at UBC’s Faculty of Applied Science. Prior to joining UBC, Dr. Wu helped develop a mouthguard with motion sensors in her PhD work at Stanford University. The mouthguard was later used to study concussions in U.S. college and youth football, and UBC varsity hockey players now wear an advanced version of this mouthguard during games and practice.

“We started a five-year collaborative study with the UBC Thunderbirds men’s and women’s hockey teams with two main research goals: to understand how the brain changes after a concussion in sports and how repeated impacts may lead to longer term brain changes,” says Dr. Wu.

“We started a five-year collaborative study with the UBC Thunderbirds men’s and women’s hockey teams with two main research goals: to understand how the brain changes after a concussion in sports and how repeated impacts may lead to longer term brain changes,” says Dr. Wu.

She says the mouthguard is an ideal tool to study these head impacts as it sits closer to the skull than other types of sensors like helmet sensors.

The mouthguard is capable of capturing data such as the speed and direction of the impact and the strength of the blow.

The study started recruiting participants last year after receiving a $944,776 grant over five years from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, working closely with Thunderbirds hockey head coaches Graham Thomas (women’s team) and Sven Butenschön (men’s team).

The study started recruiting participants last year after receiving a $944,776 grant over five years from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, working closely with Thunderbirds hockey head coaches Graham Thomas (women’s team) and Sven Butenschön (men’s team).

“Concussions are a part of the game of hockey, because it’s such a fast sport,” says Thomas. “There’s just so much that can happen. We’re doing this [research] for the bigger picture and for the benefit of those who come after us.”

Butenschön says that experiencing a concussion can be more challenging for varsity players than for professional players. “Let’s say you’re playing junior hockey or professional hockey, you get a check to the head, you can isolate, you

can relax and recover. Here at UBC, these players have midterms and exams, and they can’t miss anything because they’ll fall behind quickly with such a demanding academic load.”

Pre- and post-season assessments

In addition to wearing the mouthguards on the ice, the players are given pre- and post-season assessments to track changes in their brain health over time. These tests include MRIs, eye tracking tests, balance tests and cognitive function tests.

In addition to wearing the mouthguards on the ice, the players are given pre- and post-season assessments to track changes in their brain health over time. These tests include MRIs, eye tracking tests, balance tests and cognitive function tests.

“We’re looking at the effects of accumulated head impacts on neurological function so we’re looking at their memory, their moods, their focus, how it affects their balance and also vision,” said study lead Dr. Adam Clansey (he/him), a research associate in mechanical engineering in the faculty of applied science.

The researchers are assessing the impact of severe concussive hits as well as more minor blows to the head.

“Severe hits to the head are what most people are aware of, but even milder hits may have significant effects if they happen multiple times over the years,” says study co-principal investigator Dr. Alexander Rauscher (he/him), an associate professor in the department of paediatrics and the Canada Research Chair in Quantitative MRI.

“Ultimately, we hope to learn how long it takes the brain to recover from a concussion. With this information we can let athletes know that they should take a break after they’ve had a certain number of hits, so that they do not risk ending up with long-term negative effects,” says Dr. Rauscher.

Concussions in women understudied

Another unique aspect of the study is that it is studying both male and female players. Research suggests that women are more likely to sustain a concussion than men, but most of the research has been performed on men.

“There’s been not enough research on female athletes who’ve suffered a sport-related concussion, and so looking at and comparing to male athletes will potentially provide some insight into the sex differences that occur,” says co-principal investigator Dr. Paul van Donkelaar (he/him), a professor in the school of health and exercise sciences at UBC’s Okanagan campus.

“This research will also help us provide some guidance in terms of allowing both male and female players to play hockey as safely as possible.”

The road to safer hockey

While the study has just started, the researchers are hopeful it will lead to better preventative measures such as helmets, improved diagnostic testing and more effective post-concussion treatment.

“Ultimately, we hope to learn how long it takes the brain to recover from a concussion and also give athletes information on where they should take a break after they’ve had a certain number of hits so they do not risk ending up with long-term negative effects,” says Dr. Rauscher.

This study highlights the value of collaboration across different disciplines, adds Dr. Wu. “Concussion research really needs researchers, players and coaches to work closely together and come up with solutions that will benefit future generations of athletes.”

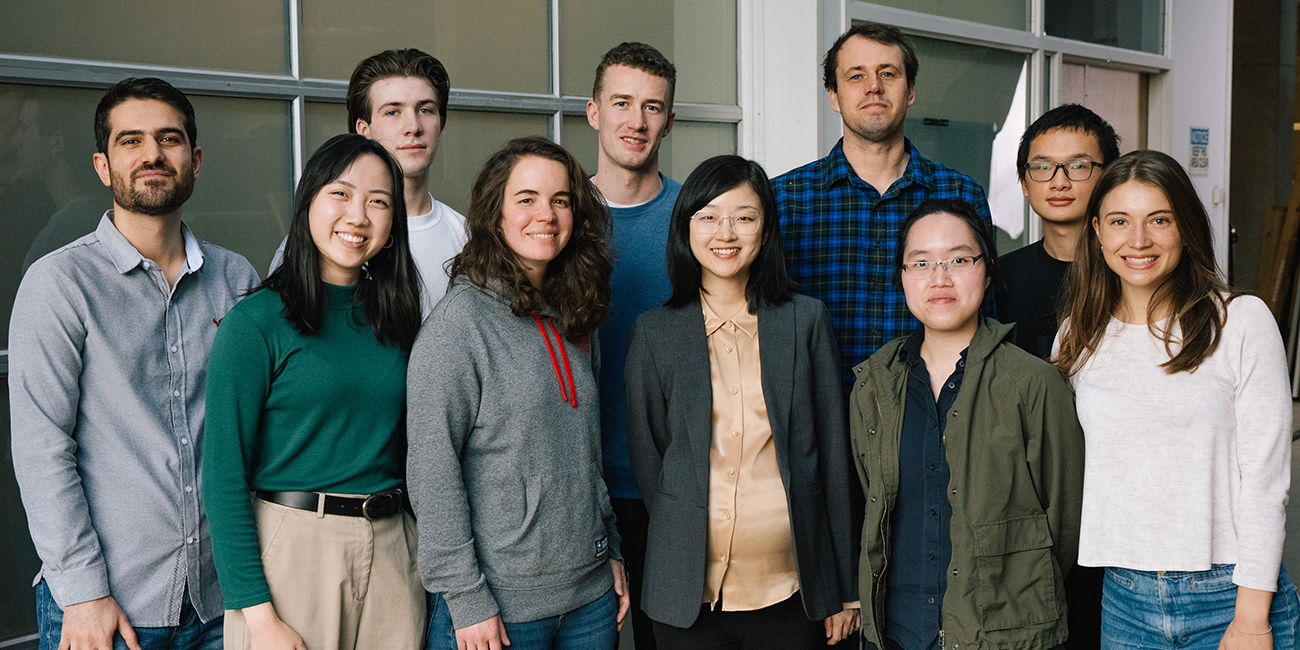

Dr. Lyndia Wu with members of her research team from UBC Mechanical Engineering:

This article originally appeared on UBC News. Photography by Kai Jacobson.